The beds don't have top sheets, just duvet covers. Most of the double beds had a pair of single duvets, for regulating separate and distinct body temperatures. All the rooms we stayed in had windows that opened easily because Germans believe strongly in Lüften. There were no screens, but no bugs either.

Our first day in Hamburg was left to individuals to schedule for themselves. My mother had made arrangements to meet up with her friend Gabi and Gabi's teenaged granddaughter, and Rachel and I elected to accompany them.

Gabi and her husband came to stay with my family for two weeks in 1973 as part of a teachers exchange program. (You should read my mother's account of that visit -- it's sweet and funny.) Gabi and Julie had been in sporadic correspondence over the subsequent half century, but this was their first in-person meeting since that long-ago summer. They picked up right where they left off.

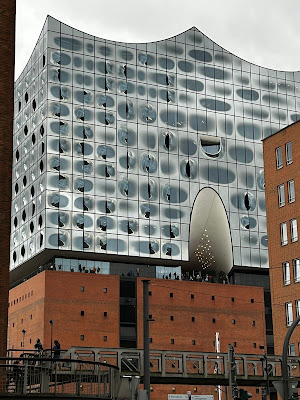

Rachel and I had also arranged to see our college friend Manjula, who grew up in the States but now lives in Hamburg. The seven of went to see the Elbphilharmonie concert hall overlooking the Elbe river. The Elphi has some resemblance to the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia -- it's a beautiful box containing two concert halls (one Groß, one Klein) and they maybe ran out of money before the job was done; in Philly, they just closed up the Western side of the box and called it finished, but in Germany it was a national project and they just grumbled through the cost overruns.

Our walk was conducted at the land speed of my parents, stretched between the speedy one and the slow one. It was a good way to periodically switch conversation partners. After taking in the view from Elphi's observation deck, we walked along the wharf, the better to see the enormous container ships that unload goods foreign destined for Europe.

|

| Gabi (left) and Julie (right) |

All along the harbor, German tourists were buying keychains and eating the town's signature herring sandwich. I made a suggestion about looking for herring Ritter Sport chocolate and I short-circuited the 16-year-old. Germans don't ever seem prepared for me to say nonsensical things, which of course makes me want to say them more.

|

| An AI-generated image of the kind of Schokolade you should be able to find in Hamburg |

At lunch in an Italian restaurant, the waitress jabbered something at dad when he tried to pick up a fallen napkin. I asked him how it felt to have all this atmospheric, environmental German language around him. "They're always telling me what to do," he said with a grin.

After a boat tour through the harbor, Rachel and I called an early evening with my parents. Most of the family had gone to see a new modern opera about a physicist and a psychic healer. A few of them stayed past the intermission, the rest went to find beer.

The next morning, we loaded our suitcases into the bus's underbelly and made the trip to the Bergen Belsen memorial, located at the former concentration camp where Pete was interred with his mother and brother for three months in 1945. Like at Ravensbrück a few days earlier, we were met by a small squad of historian guides upon our arrival. Dad gave them a printed copy of a piece he wrote in 2021 about a camp memory to add to their collection, and we started inside the museum.

Unlike the repurposed SS Officer housing used at Ravensbrück, Bergen-Belsen has newly a constructed, brutalist, concrete structure housing their exhibit. I had seen all those ghastly black and white photographs before so I knew the images, but on this trip I thought for the first time about how Dad saw it all in color, married to the fetid odor of open latrines and decaying corpses.

After we walked through the museum, it was time to visit the former camp site. It's all meadows now, with about a dozen mass graves, each a grassy mound with thousands of dead bodies lying underneath. The staff had determined that Dad and his brother were likely in hut 211, so we walked there in the misting rain. It overlooked a huge burial mound that was an open pit when Dad was last there. He remembered it. He said that he spent his days there just wandering around inside the fenced-in perimeter, because nobody was looking for him and he had no place he was expected to be.

|

| outside hut 211, where Dad and his brother were housed |

We lit a yahrzeit candle and said Kadish for my uncle Sam, who died two years ago, and then we walked back to the museum to get lunch at the cafe. The atmosphere felt sour and sad, but not scary. As before, Dad was not overwhelmed and showed no fear about confronting the place.

At the cafeteria, the historian who had taken possession of Dad's story came back with exciting news, it had exactly matched some details they knew and filled in a gap about some details they didn't. One of the children in Dad's account had reached out to the memorial site team in recent years, and the historians were excited to share Dad's story with her.

|

| Bernd Hoffman from the memorial site shares his findings about the people in Dad's story |

I fell asleep during this part of the trip. Maybe it was because of what we had just processed, or perhaps because the guide, whose English skills were sorely tested, was mumbling, or because the bus ride was lurching, but I learned after we hit the road for Hanover that my reaction had not been unique.